Let millions of flowers of faith bloom and a thousand Bible schools contend

BEFORE THE BLOODY Cultural Revolution, China allowed freedom of religion. It said so in its constitution. The only condition was that it not disrupt public order.

But as rampaging gangs of revolutionary Red Guards in the late 1960s desecrated and ransacked Buddhist temples, Christian churches, and colleges of learning, any remaining spirit of tolerance came to a violent end. There could be only one cult in China, and the orders from Beijing were to clean house with a new credo: “Remove the four olds”—old ideas, old customs, old habits, and old culture.

Professors, priests, and nuns, were publicly humiliated, beaten, sometimes to death, tortured, raped, and murdered in sadistic rages. These were times so tumultuous that the numbers of the dead could only be estimated—between 500,000 and two million. Older people and intellectuals were the main target of the youthful mobs. They placed dunce hats on their old teachers’ heads, flogged them with belts, and waved Little Red Books of sayings from Mao Zedong, the founder of modern China.

Just ten years earlier, over a brief few weeks between the winter of 1956 and the spring of 1957, Mao had resolved to “let a hundred flowers bloom and a thousand schools of thought contend.” He wanted to engage the sages, and any who felt alienated, in a collaborative dialogue of ideas. But he got more than he bargained for. Anti-communist slogans were splashed up on walls, and Mao’s mood turned from harmony to revenge.

He promised to “root out the poisonous weeds,” claimed he had always planned to “entice the snakes out of their lairs,” and jailed his critics, sent them to camps, or had them executed. When this initiative didn’t work to sway public opinion, Mao orchestrated the Cultural Revolution not just to keep alive the spirit of revolution as rivals plotted against him, but also to erase the memory of his failed farm reforms of 1958-1962 that saw 45 million starve to death.

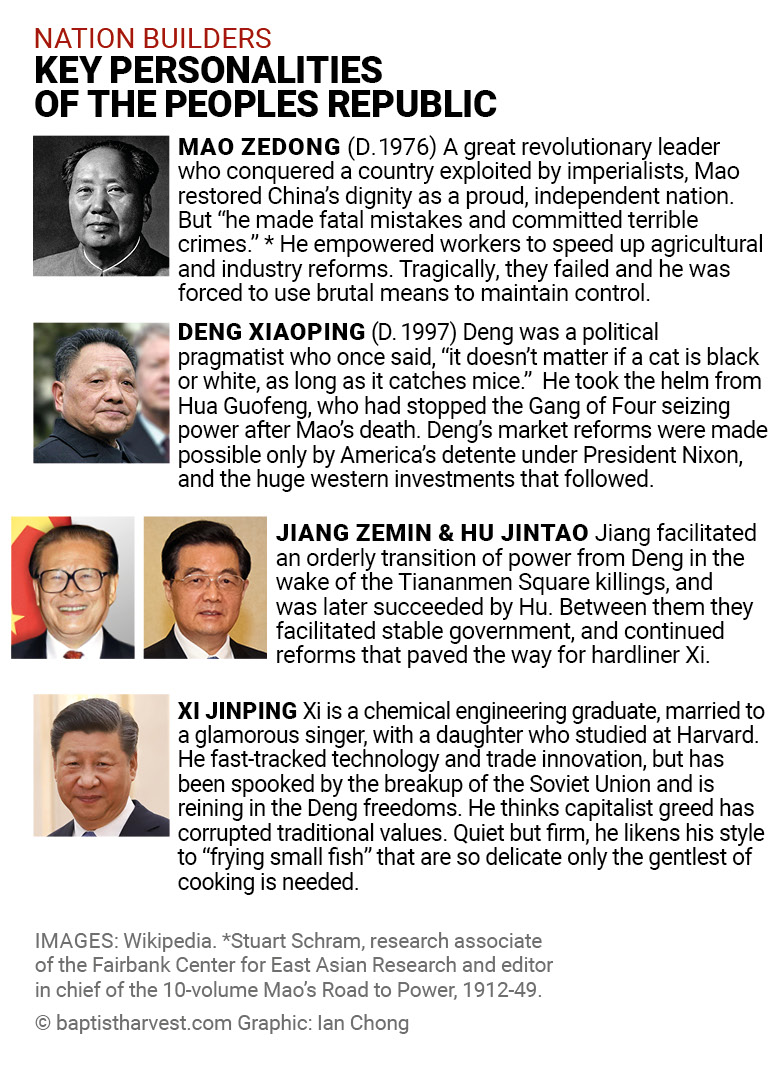

Over time, people grew weary of bloodshed, ongoing turmoil, botched economic policies, and stagnation. And soon after the death of Mao in 1976, a more liberal leadership emerged under Deng Xiaoping. Market reforms and societal freedoms sparked a rush to learn English, and economics, and modern business techniques. Engagement with western nations flourished—and God opened the door to more Independent Baptist missionaries than ever before.

When teachers became preachers

Among those western teachers and professors were soulwinners, secular educators by day, and Bible-teachers by night. Many of those saved back then are the national pastors of today, teaching others to teach others also, and multiplying churches.

Even with the current squeeze on freedoms under Xi Jinping, gospel seeds planted both underground and in plain sight are now blooming a thousand-fold.

One Mandarin-speaking professor/pastor who taught for nine years in a large industrial city, says of those times, and of students, many of whom were saved and went on to serve Christ:

“College was the first chance for an entire generation to think outside the box, away from their traditional rigid and formal schooling. Teacher-missionaries were active in winning thousands upon thousands upon thousands to Christ, with a big focus on the Pearl River Delta. Eventually the authorities became aware of this.”

One of his former students, who pastors an underground Independent Baptist church in the delta—the world’s largest built-up area with a population of 65 million—recalls:

“My first year at college, I made friends with a Chinese-speaking missionary from Ohio. I knocked at his door wanting to practice my English. I told him I was already a Christian because I had prayed to Jesus for many years. He was astonished, but told me that this did not make me a Christian. He told me I was a sinner, and needed to accept Christ as my Saviour.

“I hesitated, because this would mean I had to overthrow all my atheistic education, and I didn’t want to completely surrender to Jesus Christ. I felt more secure controlling my own life.”

But as he began to attend an underground church, he began to understand that even Confucian morality with its emphasis on inner virtue, morality, and respect for the community could not heal his sinful heart.

“I heard a visiting preacher from the United States speak on John 4—the living water. The Holy Spirit worked in my heart and my eyes were opened by God’s word. I saw that just like the woman at the well, I was lost and blind. I couldn’t fix myself. I needed Christ.”

The country also needed fixing. Around him, China was experiencing a boom. Millions were lifted out of poverty, and the fruits of prosperity were on display for all to see. Consumption was conspicuous. People felt free to spend, and to enjoy life. The popular phrase was, “Jump into the sea,” meaning that if you could swim, you could make a fortune.

But what if you can’t swim? Unfulfilled desires breed discontentment, and rulers are fully aware of the danger of unhappy subjects. God says,

Where the spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty. (2 Corinthians 3:17)

But liberty is the enemy of autocracy. As Confucius collided with Christ, the Communist Party of China had no choice but to align itself with the traditional works-based religions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Dàoism.

Missionary John Honeycutt, author of the discipleship book Journey, and son of the pioneering China and Philippines missionary John Honeycutt Sr., says the choice for China today is binary: Either Christianity is, and always has been a help to people, or it is a threat to the stability of the country.

“Under Xi Jinping, the decision has been made that Christianity is a threat,” he says. “He definitely knows that where Christianity goes, freedom and liberty goes. So the only choice is repression.”

Where Christianity goes, freedom and liberty goes. So the only choice is repression.

Cash incentives to betray ‘foreign spies’

Xi has Sinicized (made Chinese) the concept of “religion,” bringing in laws that insist all religions conform to the doctrines of the Communist Party of China (CCP) and the traditions of the majority Han Chinese population.

Sources in China told harvest magazine that most of the Bible-believing foreign missionaries have left, their visas not renewed. And gatherings involving locals and foreigners are being watched, with cash incentives offered for neighbors who betray “foreign spies.”

At least 70 western or western-educated Chinese national Independent Baptist missionaries are known to be still operating in China. The true number of trained pastors is unknown due to the secret nature of their existence, and may actually run into the hundreds, even thousands. What we do know is that their work is continuing apace.

Many we know of have returned from offshore after furloughs forced on them by the travel restrictions of Covid years—they were stuck outside the country, unable to return—and have settled back into their churches, albeit with greater wariness and watchfulness. But they fear that digital communications with offshore supporters and local church members are now well nigh impossible.

“We understand it will be more difficult to minister in this closed country, but our confidence is upon our mighty and all-wise God and Lord Jesus Christ, and not on us,” one returning pastor told us.

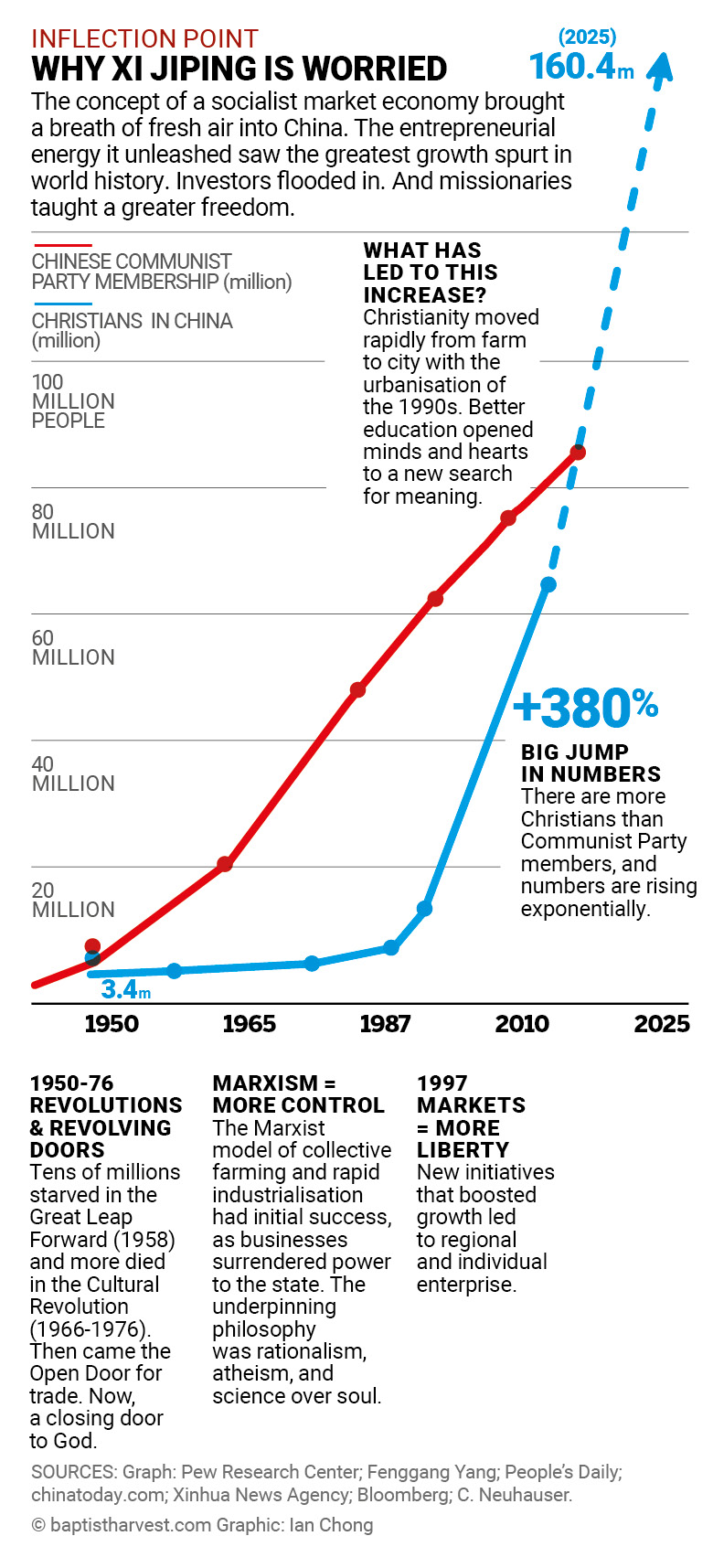

The crackdown has come all too late. Those “hundred flowers” of free-thinkers who chose Christ not many years ago, have bloomed into hundreds of thousands of small churches. If we include state-registered churches where—despite party monitors within their ranks—many are being soundly saved, Christians outnumber members of the Communist Party of China. According to official party statistics, Christians will soon number more than 160 million, almost double the current party membership.

Bible churches increased rapidly during the time that the rising generations under Premier Deng were enjoying a rapid and comprehensive education. They also exhibited a thirst for knowledge of spiritual matters. One teacher/pastor told us: “All I needed to do was faithfully to explain the gospel, the meaning of sin and judgment, and the living waters available to all who acknowledged their need of a Saviour, and people understood, and got saved.”

In one major city visited in the early 2000s, house churches swelled to more than 100,000 members, and have multiplied amoeba-like ever since. Recalls Darrell Moore, then with the Fundamental Baptist Missions International (FBMI) missions board: “I met met two underground church leaders who were managing churches at 1,500 meeting points around the city, with a total membership of 100,000. They had numerous pastors going from house church to house church, and conducting services, seven days a week. I was astonished at the age of these two men—one was 24 and the other 25—overseeing a mammoth house church movement.”

He tells of an evening when he gave a Bible study in a church inside an apartment complex. Men walked around in the street outside, watching, while others were at every window upstairs, alert for security police.

“Members of the congregation were standing or sitting on every square inch of the apartment. Someone led the singing. They didn’t sing loudly because they did not want to be discovered. I was overwhelmed by the whole experience. It is indelibly printed on my mind—the passion they have for God, and the word of God. In the United States we don’t go to church if we have a hangnail, but they will go and sit there, knowing full well that the security bureau could raid that apartment and throw them all in jail, or kill them. Their devotion is unbelievable. That experience in itself has motivated me ever since,” Moore says.

Those young pastors of the underground church movement were the fruit of older men who had been arrested, beaten and tortured for their faith.

A manual for persecution: tips on how to die

As a teenager, John Honeycutt remembers meeting five of the leaders of “huge fellowships” of house churches:

“These were men in their 70s and up, who still carried the physical scars of persecution, prison, and violence. They all had the same type of discipleship book, about six inches thick. Half of the book contained pretty good Bible teaching, and the other half described practical things to avoid persecution, such as the lies the police will tell you, the torture you can expect.”

He says there was a section on, “How to die, if you need to, when the torture is too much to bear.”

“They would all ask the same question of visiting westerners: ‘Are you willing to put your neck on the line for Christ?’ Was I willing to die for the gospel’s sake? Before they would partner with us, they wanted to know our level of commitment.”

Thanks to western financing, there is no shortage of Bibles and discipleship materials, and online delivery mechanisms. Honeycutt’s Journeys series has been downloaded more than 120,000 times and is being printed at multiple locations inside China.

He says the very tactic of banning large gatherings has helped churches to multiply.

“The fact that they can multiply one-on-one is the Achilles heel to China, as it was—and is still—in Russia. The reason the number of Christians grew to between 150 to 175 million in China is that the Lord has arranged the rules so people can meet only one-on one, even every day with a new Christian. There’s no law against one-on-one. Then, when they the pastors are sure of the person [being a genuine convert] they bring them into a house church. When the church gets to more than 50, they split it off and start another house church.”

Honeycutt knows of 11 national pastors who obeyed God’s call to start churches in a particular area. Yet not one of them knew of anyone else. “It was just the Holy Spirit directing them go there. Sadly, we also had 23 pastors who became ill and passed away during the Covid pandemic, so we worked with their home churches offshore to help their families get re-settled, and then to get someone new into their churches. We are in the last days for sure,” he says of both the growth, and the opposition pastors are facing.

The day the shutters came down

The shutters came down early in Xi’s ascendancy for the veteran China hand, Ken Lalman, who had built a church of 250 on the outskirts of the capital, Beijing. The church had a 200-seat auditorium that overflowed to 350 on high day, and boasted a staff of 15, and a school of 40 students.

Many of Lalman’s converts went on to at Independent Baptist colleges, including West Coast Baptist College in Lancaster, Golden State in Santa Clara, California, and Heartland in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The pastor now works with Chinese migrants at a church in California, where he numbers among his congregation some who had been tortured in Chinese jails but managed to escape to the west.

Lalman, who evangelized and planted churches for more than 20 years in China, under the auspices of Baptist International Missions (BIMI) says all was going well until the day that some of his teachers were pulled over by the police who found out about the church. Thereafter, police started dropping in once a month.

“After a while, a group of 15 police and government officials arrived and took me away for questioning. My visa was revoked and myself and my family were given 20 days to leave.”

Lalman says the police, like the population generally, understand that Christians are harmless. “I told them, ‘I just want you to know that Christianity has helped a lot of people. I know families that have been restored, couples have been restored, parents and children restored. Just wanted to say that. We’ve done a lot of good things, and helped people’.

“They were polite. They said, ‘We know you’re not a bad person. We know you’re good person, but it is illegal to have a church. We’re not kicking you out, we’re just asking you to leave and you can’t come back’.

“You can’t argue with them. The way the Chinese work, before they talk to you, they know everything about you. You could talk to them until you’re blue in the face and you’re not going to change anything.”

Lalman, who pastors Silicon Valley Chinese Baptist Church in Santa Clara, California, says he spoke with some human rights lawyers recently who had been assisted out of China by United States Government officials.

“They had horrible stories of abuse in prison,” he says. “Now they are safe here, but they can get only landscaping work. They are taking whatever they can get. They are starting their lives all over again.”

He says Chinese communists are anti-Christian because the key countries opposing them politically are Christian: America, Britain, and Australia, among other American allies.

The Beijing-born, American-educated writer Jianying Zha says large sections of the population have come to the conclusion that communist ideology in the form of a state religion is empty.

“Deep down, that idea wears out after some time, and people realise there is still this hollowness—a certain spiritual thirst—that is not being fulfilled,” Zha told viewers in The China Century series produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Asia Society director Orville Schell agrees that the missing piece of the China dream is spiritual. “This interior realm of any human being is highly individual, and it can be highly insubordinate—all of the things the Communist Party has never esteemed.”

But in order to create a safety valve for a growing demand for a need not able to be fulfilled by the party—which Zha describes as “the biggest cult of all”—authorities allowed religions to come out into the open. This included Chinese traditions of all kinds, including Dàoist spiritism.

Fact-checking the anti-western spin

Schell concedes that “allowing some kind of religious belief did take a certain pressure off.” But the author of 15 books on China and former dean of the University of California’s school of journalism adds: “People started to develop things called home churches that were outside of the structure, that made the party very wary.”

To Karl Marx, and Xi Jinping, religion is an irrational comfort for feeble minds. Marx called it, “The sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soul-less conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

“Science, not superstition,” is at the heart of Xi’s nationalistic cry, with an emphasis on the technological achievements of the Chinese people. He reaches into the past and the “century of humiliation” under colonial powers as a whipping boy to demonize the west and its Christian values.

But the facts do not align with rhetoric. The exploitative age of colonial empires is long gone, overtaken by economic alliances—including China’s own Belt and Road partnerships that burden needy nations with debt. And lest Xi forget, it was the west’s willingness to put aside political differences and transfer its modern technologies to Chinese factories, that helped to lift 800 million of China’s people out of poverty.

Christianity with western links represents a real danger to Xi, who was shaken by the breakup of the Soviet Union, and supports Moscow’s efforts to reunite its old empire. He blames western infiltration, with its focus on individualism and the avarice generated by capitalist consumerism, for the former Soviet republics deciding to pursue independence. To avoid a similar fate in China, he has cracked down on corruption, reined in the excesses of wealth, and is on a path back to Marxist values.

Anti-Christian actions are systematic, and widespread. The government already monitors state-registered churches, and is seeking to rewrite the biblical materials used by the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, the officially sanctioned grouping of Protestant churches. But even the Three-Self churches, according to those who have visited them, often preach a clear gospel message, and attract many who are saved by grace, through faith.

Street vendor pastor-preachers by the thousand—‘This is where the action is.’

One visitor to a Three-Self church told harvest magazine: “I went to the church in a multi-storey building. It had an auditorium seating between 500 and 600 people. There were cameras and listening devices all over the room for the government to eavesdrop on everything. But a lady got up and gave a clear presentation of the gospel—scripturally driven. Then a man announced the Lord’s supper—but only for those who had trusted Christ as Saviour. At the end of the service, those with questions were invited to go downstairs to an ‘inquirers’ room’ where they would be instructed about salvation.”

Another source insisted that the number of true Christians in Three-Self churches is relatively small. Beijing has instructed those churches not to teach the virgin birth of Christ or the resurrection, because it contradicts the Marxist emphasis on rational thinking. The chances of salvation under such teachers are non-existent, he says.

Thousands of small churches continue to be planted across China. Western organizations such as those under the umbrella of the World in Need International Baptist Mission help to finance small businesses, such as street vendors. “This is where the action is,” says Honeycutt, who has himself planted four churches in the Philippines, one in Hong Kong, and who partners with more than 500 other works in 20 countries.

“Each vendor costs between $1,000 and $3,000 to get up and running, and so far they have started 3,200 congregations and fellowships. There are not enough pastors to go round, so there might be one pastor for 10,000 believers. But using our discipleship materials, it is possible for them to train assistants with video materials, voiceovers of the lessons, and so forth.”

One national pastor we interviewed says government tactics like rewarding neighbors to spy on neighbors were part of the deliberate process of eroding trust and keeping populations in fear.

“Not many people trust others. We live in perilous world. In China, it’s all based on relationships. I start a conversation based on a common interest—what they care about. ‘Hey, I hear your kids speaking English. My kids also can speak good English.’ You see, Christ did not start with religion. He would start with something simple, such as, ‘Hey could you give me water to drink?’ My purpose is to start a conversation, and then let them know I care about their soul: ‘Are you concerned about your soul? What do you think about eternity?’ And from there, turn to the gospel.”